John Monteith - Resonances

2018 | JOHN MONTEITH

RESONANCES

TORONTO

7 avr - 12 mai

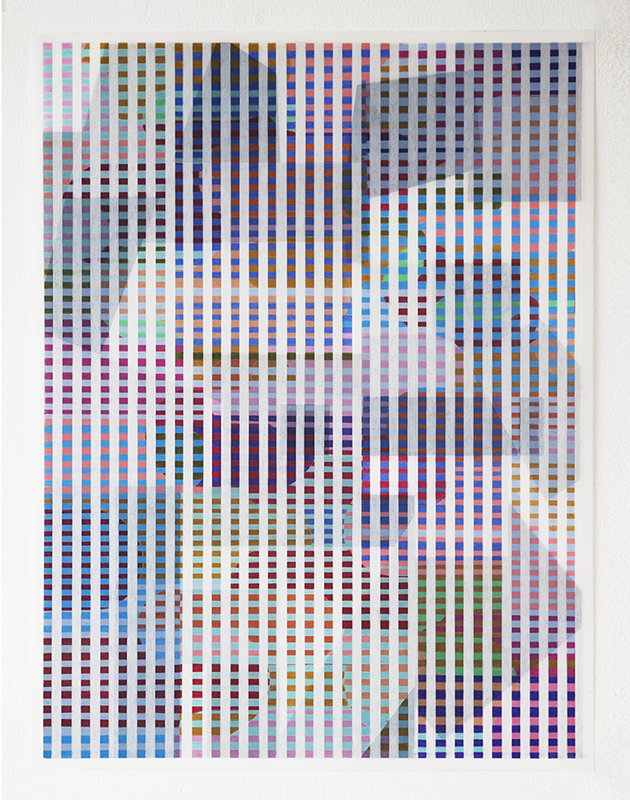

6 & 48, 2017-18, Cire et crayon sur Mylar, 24” x 18”

RESONANCES

7 avr - 12 mai

The anxiety caused by the world becomes dissipated through abstraction, through a figure that is not part of a future defined by rationalizing technologies and financial transactions: a form that allows you to rethink yourself in relationship to other people.

– Doug Ashford ¹

A voice with resonance is strong, an idea with resonance carries weight, and a sound with resonance vibrates in sympathy with neighbouring sound waves. Resonances are the suggestive and powerful in-between spaces of relating one with another; they are spaces of indeterminacy and possibility. In celestial phenomenon, a resonance is the synchronous gravitational force between two bodies that orbit a third—a triadic force of moving parts breaking with dyadic, binary relations as they move together. Resonances respond, and strengthen over time.

These etymological reflections offer one way into the abstractions of John Monteith’s newest body of work. The objects of inquiry that underlie the surfaces of his precise geometric abstractions are not sonic or astronomic resonances however but the various relational sites of social exchange that make up the urban environment. Skyscrapers and skylines, towers and buildings, zones, paths, parks, highways and roadways are here recast in a series of overlapping, repeating, reformulated geometries—a system of exchanges articulated through reverberations of form. In reality, the designed spaces of civic sociality are determined by urban plans, aerial and subterranean cartographies, and buzzing energy grids, each a system of differentiated logics that is already abstracted from our experience of daily life.

Resonances is a series of visual exchanges that oscillate between two- and threedimensionality, obscuring the gestural hand which performs the requisite and repetitive labour of production behind the not-quite-transparent sheen of the surface. Fluidly collapsing the photographic with the drawn, this mode of expression resolves itself in precise shapes, lines, angles and grids realized on vellum. The eye flutters to look, skipping and darting across patterns, following paths and forging visual connections, in ways akin to our traverses in the city: as peripatetic wanderers and creatures of habit. In vivid colour, the spatial logistics and organizational structures of a city become kaleidoscopic, even hallucinatory.

Through photography, stilled video, sculpture, drawing, painting, weaving, performance, collaboration, and curatorial initiatives, Monteith encompasses an intelligently interdisciplinary approach to all his work. Across these media and throughout his career he’s developed a familiar aesthetic, one which veils its conceptual underpinnings. Processes that include layering, distorting, cropping, rearranging, flattening, and reducing build new ways of understanding the indeterminate spaces between digital and analogue, between the virtual and the actual. Hardly the stuff of post-internet hype, his work hovers between the formal concerns of modernist abstraction and the speed of digital compression. Perhaps the Resonances series, with its brilliant colour and proliferation of Instagram-ready compositions, articulates this more than most: in person we feel them, online we consume them.

Produced in conversation with cities that bear an incredibly diverse history of the built form— Berlin, Toronto, New York, Beijing, Pyongyang, Halifax, Kyoto, Ho Chi Minh City, Hanoi, Havana, and Taipei—Monteith’s work, at its core, is an articulation of the representational politics of space, without being named as such. In dreamily layered and responsive patterns, imagined spaces seem to construct themselves autonomously, forming out of the accreted memories that urban architecture embodies as cities evolve. Referentially melancholic and at times purely formal, his work seems to ask what is lost when we willfully forget, what is eclipsed when we overwrite the city in code? As change proliferates, gentrification becomes a shorthand for the ways in which a city articulates loss; what we remember or what we let go is fleeting, and determined by the conditions of our subjectivity.

Working very much in relation to the body but without figuration, Monteith’s repetitive and obsessive mark-marking calls attention to his own physicality through the production of work that is a necessity of aesthetic practice. This body need not announce itself directly but if one looks closely, the carefully considered recto-verso relationships suggest much about the unseen emotional, physical, and affective labour that is performed in our cities, often by marginalized communities and so frequently behind the scenes and screens of cultural production.

And here is where Monteith’s work might be read through the emergent discourses of queer abstraction: in the absence of a represented body, in its precise refusal to represent the literal forms of figurative visibility that have so often been the subject of queer artists, Monteith complicates our understanding of queerness as “difference,” as it comes to bear meaning in the spatial organization of the city. While the term “queer abstraction” may itself be fluid—“an investment in indeterminacy,” allowing artists to talk about the body without being bound to represent it—this fluidity works to open conversations once again to the political valences of abstraction.² One could rightly claim that the abstraction of high modernism, surely a touchpoint in this series, was always politically motivated, and always a response to the conditions of subjugation under which it was formulated.

Abstraction need not refuse representation full-stop, but it can allow us to think more expansively about the world we inhabit. As Monteith has remarked: “We fail to recognize ourselves in abstraction, because abstraction is not a direct representation of our known world.” ³ It is precisely because of this lack of recognition that a plurality of responses is possible, flooding the frame with the extent of subjective and contingent human experiences. In their refusal of figuration, in their capacity to be formed and reformed as living documents exposed to the possibility of erasure and transformation, the works in this exhibition hold open a fluid space that operates against the rigid codes to which urban communities have historically been held.

² Ashton Cooper with Loren Britton, Kerry Downey et. al. "Queer Abstraction: A Roundtable." ASAP/Journal 2, no. 2 (2017): 285-306. In the introduction to this round table, Cooper suggests that we consider “queer abstraction as an investment in indeterminacy that allows for an expansive sense of embodiment—which includes, but is not limited to, the slipperiness of gender, affect, desire, and language.”

³ In conversation with the artist, July, 2017.